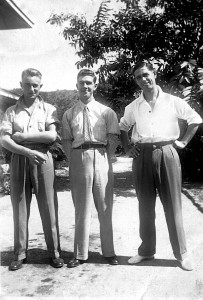

Albert (centre) in Trinidad where the survivors were landed on 7 December 1941. Two other survivors, Robert Rainbow (left) and Jim Davis are with him.

Albert posted the following account on the BBC’s people’s War web site:

I was born in 1921 and joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve at HMS Eaglet in Salthouse Dock in 1938; my division number was M.D.X. 2811. When war broke out I was mobilised with other R.N.R ratings and three badge pensioners. After being kitted out at HMS Drake in Davenport we were entrained up to Glasgow to join HMS Cilicia, an armed merchant cruiser. We set out for Greenock for provisioning and loading with ammunition and then sailed for work up trials and gunnery practice, before returning to Greenock. After a week?s leave we sailed to take up northern patrols around Iceland, Greenland, and the Denmark Straits, with orders to stop and search

any vessels which could be carrying war supplies to Germany. We were next ordered to escort convoys leaving Britain for 200 miles into the Atlantic, and then return again escorting convoys bound for Britain; this lasted for eighteen months. The next convoy mission took us to Capetown and Durban, and further escort missions to Freetown South Africa and Bathurst in Gambia. Arriving back in Freetown, South Africa I was given a draft to join HMS Birmingham, and while on the depot ship Edinburgh Castle waiting for HMS Birmingham to arrive, I was posted to the Flower type Corvette HMS Anchusa, which had a number of crew sick with malaria. We escorted small convoys three days out, returning with other vessels from the main convoys into the harbour. Returning to Freetown I found out HMS Birmingham had arrived and sailed again, so I was promised a move to the next ship which happened to be HMS Dunedin, a light cruiser. We sailed from Freetown and for some time we were making dawn visits to the islets off the coast of Spain, where it was reported that U-Boats were re-fuelling, but no sightings were made so we left to patrol the South Atlantic. Again we were looking for ships which could be carrying supplies for the enemy, or U-Boats refuelling in the area but no sightings were made.

Some months later at about 13.15 on 24th November 1941 I was off watch and coming up the steel ladder to the starboard side upper deck when there was a huge explosion forward and huge flames erupted. The ship shook and slowed and the anchor chain was unshipped from its shackles and ran straight out. A second torpedo struck aft under the officers? quarters and the ship began to list to starboard. Boats could not be lowered on the starboard side, and none could be shipped on the port side due to the list of the

vessel.

I scrambled over the side and could see the barnacles coming up to meet me so I plunged into the sea among the debris and fuel oil. My main thought was to swim away from the ship as far as possible before it sank. Lots of the crew were already in the sea but many more were still on the ship because they couldn’t swim. The ship started going down bow first and it was a horrible sight to see the stern in the air with one of the propellers spinning idly. Some men in the water were screaming and shouting because they could not physically swim any further, but I managed to get hold of a Carly float and haul myself on to it. The U-boat U 124 which had torpedoed us surfaced, the conning tower opened and an officer began to take a film of the ship sinking. We were very relieved that the U-boat Captain, Johan Mohr, ignored the edict from Hitler that survivors at sea were to be machine gunned in the water.

The floats tried to stay together, although one drifted off during the first evening. As men died they were gently put over the side and a prayer was said. On my float was the assistant canteen manager, a pleasant chubby chap in his early twenties who was found dead in the bottom of the float one morning. Some men were naked and some in just underpants, and at night we would have given anything for a blanket. Drinking water became a problem so

when it rained we collected what we could. Other problems were the Sharks, Barracuda and Dogfish who would attack men who were not able to get completely on the floats.

Eventually in the evening of the fourth day, we were picked up by the SS.Nishmaha an American freighter out of Galveston Texas. This rescue happened because Roy Murray, a keen eyed Third Mate on the bridge spotted one Carly float. Other officers were called to ?look out? duties and by circling around the Nishmaha eventually rescued the five rafts left from an original seven. The crew were very kind, giving up their quarters and erecting an awning aft for the survivors. At least three marines were laid out dead when they got on board and I think there were other seamen who died during or after they were rescued. Five men were buried at sea with full

honours after being rescued.

Out of a total complement of 486 officers and crew of HMS Dunedin there were only 67 survivors.

After five days sailing we were landed in Trinidad, and ambulances waiting on the quayside took us to the naval hospital HMS Benbow, where we were looked after by Lt. Hand. After two weeks, local civilian families came and took us to their homes for the Christmas Holidays. I was with a family named Aird; the husband worked for the Sun Life Assurance of Canada. I and the other survivors were guests at the Governor’s house for lunch. During

the afternoon an Army band was playing with soldiers counter-marching up and down on the lawn. Each of the survivors was given a small present, mine was a wallet. We were all kitted out with new suits, shirts and ties by A.J.Green a local factory, and various stores supplied us with cigarettes. The local community were extremely kind and supportive to us.

I returned to England in mid January 1942 aboard the New Zealand troopship SS Awatea which docked in my home town of Liverpool. My family were overjoyed to see me, especially my mother, as she had received the usual wartime telegram that I was ?missing presumed dead.? I was given a draft chit to the HMS Eaglet which was a naval ploy to give me three weeks at home in Liverpool before reporting to HMS Drake at Davenport. You don’t realise how much your home and family mean to you until you have been

through something like this.

During my time at HMS Drake I was initially treated with suspicion, as my papers had not arrived with me, however some other sailors arrived who recognised me; they managed to convince the Master at Arms of my identity so I was posted to the fo’csle mess, Blue Water, under divisional commander Lt. Commander Frost. While there some of us were given arms and sent to act as sentries for the Radio and Signalling station at Stoke Dammeral.

My next move was to a depot ship at Rosyth, which was used to supply relief crews to ships whose crews were going on leave. While I was there Commander Frost took me on board HMS Cilicia, and presented me to King George VI who was inspecting the fleet; this was a great privilege and honour.

From Rosyth I was posted to HMS Renown in October which had joined Force H in the Mediterranean after her refit. We escorted Scottish and Free French forces for the assault on North Africa at Oran, and then mixed forces for the invasion of Italy.

HMS Renown returned to Rosyth in February 1943 for a three month refit. In August we sailed to Halifax Nova Scotia carrying the Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the Quebec conference in Canada, and returned via Oran where Mr Churchill left to attend the Alexandria and Casablanca conferences.

The catapult was removed from HMS Renown at Rosyth in the beginning of December 1943 and replaced with Torpedo Tubes and Oerlikon Guns, and then we sailed for Scapa Flow where Vice Admiral Sir Arthur Power raised the flag. After leaving Scapa we arrived in Colombo Sri Lanka on 27th January 1944, on our way to join the fleet in operations in the Far East. On 19th April we were involved in a strike on Sebang, then in May a further strike on Java at Surabaya; re- provisioning and ammunition were taken on board in Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia.

We then joined other ships, HMS Illustrious, HMS Valiant, Queen

Elizabeth, HMS Richelieu, HMS Cumberland, and a the Dutch Light Cruiser Tromp, together with seven Destroyers for a strike on Port Blair in the Andaman Islands. On 27th July we went on to Trincomalee where HMS Valiant caused a certain amount of consternation by being trapped in a sinking dry dock. August saw us attacking installations on Car Nicobar and other small islands, also during September we attacked other islands in the Nicobar group. In October we returned to attack Nicobar installations again, and then sailed to Durban at the end of 1944 for a refit.

When the refit at Durban was complete in 1945, HMS Renown returned to Britain. During the voyage we received news that the war was over, and Japan had surrendered; this caused great celebration and a feeling of relief.

Arriving back in Britain I was given a period of leave, and at the end of this I received my discharge papers.